Six Things to Know about The DTES Ethical Research Manifesto

Back in February 2020, which now seems like a lifetime ago, West Coast LEAF signed on as an organizational endorser of Research 101: A Manifesto for Ethical Research in the Downtown Eastside.

The Manifesto was developed by peer workers in the Downtown Eastside (DTES) through a six-part workshop series, in collaboration with SFU researchers. It “provide[s] guidelines for researchers which clearly outline the expectations that DTES community members have for research that is respectful, useful, and ethical in the DTES community,”[1] This project is part of an ongoing conversation within the DTES neighbourhood about community ethics, in response to a long history of people extracting knowledge and stories from the community in ways that have caused harm.

Endorsing the Manifesto is one part of West Coast LEAF’s ongoing process to reflect, learn, and grow in our research-based processes. Research informs all of our reports, education projects, submissions, and legal strategies. Embedding our research process in community knowledge and experiences means developing and evaluating processes and protocols that strive to not harm the community we intend to be working alongside.

We are still in early stages of embedding the Manifesto into our protocols, but we wanted to share our six reasons why we feel the Research Manifesto is a good fit for our organization (and maybe yours too!).

1. It is part of addressing the complicated history of research done on communities and people.

Research is not a neutral process, it is influenced by our values and worldviews. Understanding the history of research and what it has been used to justify is important when working alongside communities that have strong reason to be hesitant or refuse to participate in research processes.

Horrible acts of violence have been committed in the name research. One such example, highlighted in the findings from the Truth and Reconciliation of Canada, are the experiments performed on Indigenous children in residential schools. This abuse of power in the name of research is not something in the distant past.

Research is also done to rather than with communities in more subtle ways, for example through funding cycles that don’t allow for the full participation of communities before asking for their consent to the research project, or through structures that prioritize knowledge being taken out of the community and not brought back to be either validated or understood by that community.

Research that reinforces stereotypes has real-world repercussions for the people associated with the stigma.

The DTES Research Manifesto reminds us of this history and provides some pathways to consider how we can address this in our work.

2. It asks researchers to be aware and not be part of reinforcing stigma.

For too long the story of the DTES has been one-sided and sensationalized. Important publications like Megaphone Magazine and the podcast Crackdown complicate these depictions, centering the voices of residents and creating a space for nuance, complexity, and the strength of the neighborhood to take centre stage.

Research that reinforces stereotypes has real-world repercussions for the people associated with the stigma. As Pivot Legal Society found in their report, stigma influences our laws and policies. But, as the Manifesto advocates, good research challenges stigma and benefits the community.

3. It unsettles the role of expert.

The title and role of “researcher” are loaded. Too often, outsiders come into communities and “scoop” up knowledge, building their careers this way, sometimes without ever giving back to the community or acknowledging whose knowledge supported their movement towards becoming an “expert.”

The Manifesto drives home the importance and role of peer researchers. This means that everyone on the research team is a “peer” with one another and everyone brings forward vital contributions. They include a list of expectations when it comes to working alongside peer researchers, my personal favorites on that list being “stop with the elitism,” and “don’t read us the book we wrote.”

We are grateful and inspired by the work that went into developing Research 101: A Manifesto for Ethical Research in the Downtown Eastside. We are proud to be signatories and continuing to learn and grow from this work.

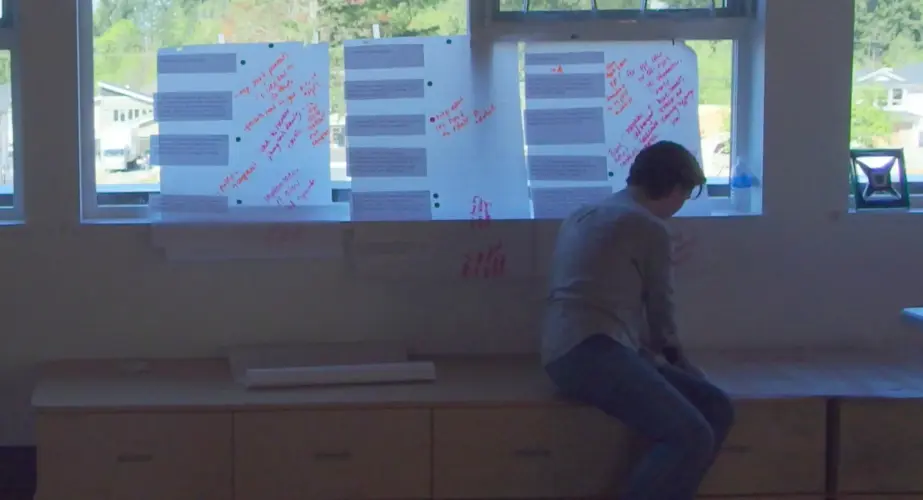

Preparing for a day of story-telling circles. Photo Credit: Sharnelle Jenkins-Thompson

Questions? Feedback? blog [at]westcoastleaf[.]org

Sharnelle Jenkins-Thompson (she/her) is the Manager of Community Outreach and recent master’s student graduate who opted out of a thesis option partially inspired by reading REB applications.

[1] KT Pathways, https://ktpathways.ca/resources/research-101-manifesto-ethical-research-downtown-eastside